Chengyu with multiple interpretations

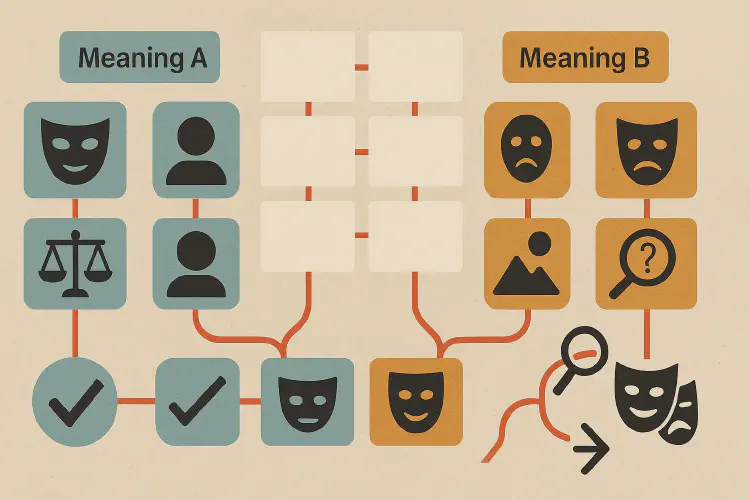

Some high-level chengyu (成语) carry **more than one interpretation** across time, register, or context. Others are **commonly misread**, creating a *practical* two-meaning reality (what writers intend vs. what readers think). Learn each idiom’s competing readings, safest usage, and quick tests.

- Chengyu Idioms

- 4 min read

Why Multiple Interpretations Happen

- Classical vs. modern drift: meanings shift from original texts to modern media.

- Polarity flips through misuse: frequent misuse becomes common reading.

- Register split: formal writing vs. casual conversation interpret tone differently.

Ambiguous or Often Misread Chengyu (with safe guidance)

-

差强人意 (chà qiáng rén yì)

- Reading A (classical/accurate): barely acceptable; not ideal.

- Reading B (common misread): quite satisfying.

- Safest use: mild understatement for “so-so, acceptable at best.”

- Example: “This first draft is 差强人意—let’s polish transitions.”

-

无可厚非 (wú kě hòu fēi)

- Reading A: not to be severely blamed (still has minor faults).

- Reading B (misread praise): flawless, commendable.

- Safest use: neutral–forgiving judgment, not strong praise.

- Example: “Given the deadline, the solution is 无可厚非.”

-

空穴来风 (kōng xué lái fēng)

- Reading A (classical): rumors have a source; there’s likely some cause.

- Reading B (modern misread): baseless rumor.

- Safest use: write the fuller line ‘空穴来风,未必无因’ to show you mean “there’s likely a cause.”

-

屡见不鲜 (lǚ jiàn bù xiān)

- Reading A: so common it’s no longer novel.

- Reading B (misread): rare, unusual.

- Safest use: “commonplace; nothing new.”

- Example: “Clickbait like this is 屡见不鲜.”

-

望其项背 (wàng qí xiàng bèi)

- Reading A: able to catch up to someone; almost comparable.

- Reading B (misread): nowhere near; can’t compare.

- Safest use: “nearly match (but still slightly behind).”

- Example: “Few teams can 望其项背 in defense.”

-

炙手可热 (zhì shǒu kě rè)

- Reading A (classical): so powerful/in favor that others ‘can’t touch’—often tinged negative (arrogant, over-mighty).

- Reading B (modern hype): hugely popular (neutral/positive).

- Safest use: keep the caution/critique shade unless context is clearly celebratory.

- Example: “A few 炙手可热 influencers distort the market.”

-

不以为然 (bù yǐ wéi rán)

- Reading A: to disapprove / not agree.

- Reading B (misread): to ‘not care’ / be indifferent.

- Safest use: disagreement with a view, not apathy.

- Example: “Experts 不以为然 at the claim.”

-

将信将疑 (jiāng xìn jiāng yí)

- Reading A: half-believing, half-doubting (neutral).

- Reading B: strong disbelief.

- Safest use: hedged stance: some trust + some doubt.

- Example: “Investors are 将信将疑 until data lands.”

-

半斤八两 (bàn jīn bā liǎng)

- Reading A: six of one, half a dozen of the other (roughly equal; often negative/teasing).

- Reading B: exactly the same quality (neutral).

- Safest use: “no real difference (often mildly critical).”

-

朝三暮四 (zhāo sān mù sì)

- Reading A: fickle, changes tune for advantage (negative).

- Reading B (story sense): tactical reframing (value-neutral) in some analyses.

- Safest use: fickleness/opportunism unless you explain the neutral angle.

-

闭门造车 (bì mén zào chē)

- Reading A: build without outside input → out of touch (negative).

- Reading B (modern misread): independent innovation.

- Safest use: keep the negative sense unless you rephrase.

Look-Alike Twins (easy to confuse → opposite meanings)

- 不负众望 (bù fù zhòng wàng) — lives up to expectations (positive).

- 不孚众望 (bù fú zhòng wàng) — fails to win public trust/expectations (negative).

Tip: If you’re not 100% sure, prefer 不负众望 for praise.

How to Disambiguate in Your Writing (3 quick tricks)

- Add a plain gloss after the idiom: “无可厚非(not perfect but acceptable)”.

- Pair with a polarity clue: data or adjective that fixes tone: “数据仍低—只能说差强人意。”

- Use fuller set phrases when risky: “空穴来风,未必无因(there may be a cause)”.

Placement Patterns That Reduce Ambiguity

- Predicate + evidence: “表现无可厚非:准时率 96%。”

- Contrast frame: “并非差强人意,而是明显进步。” / “进步不小,但仍差强人意。”

- Definition apposition: “报道称空穴来风——消息源来自三方记录。”

Mini Dialogues (natural, disambiguated)

- A: “So the outcome was great?”

B: “Not great—无可厚非而已(acceptable, not stellar)。” - A: “Is the rumor nonsense?”

B: “难说。空穴来风,未必无因—let’s verify the source.”

Quick Practice (choose the safest interpretation)

- First version is barely acceptable → 差强人意.

- Acceptable under constraints (not high praise) → 无可厚非.

- A rumor likely has some basis → 空穴来风(未必无因).

- Almost, but still slightly behind a top team → 望其项背.

- So popular/powerful it’s “too hot to touch” (hint of critique) → 炙手可热.

Common Pitfalls (and fixes)

- Assuming classroom myths are right: check a learner’s dictionary entry; many viral posts get 差强人意 / 空穴来风 wrong.

- Dropping idioms without context: always add a fact or gloss to anchor tone.

- Praise words that aren’t praise: 无可厚非 is not a compliment; it’s “acceptable.”

Takeaway: Some chengyu are meaning-shifters. For clarity, (1) know both readings, (2) signal your intended polarity with a gloss or data, and (3) prefer conservative, widely accepted interpretations—especially in exams or formal writing.