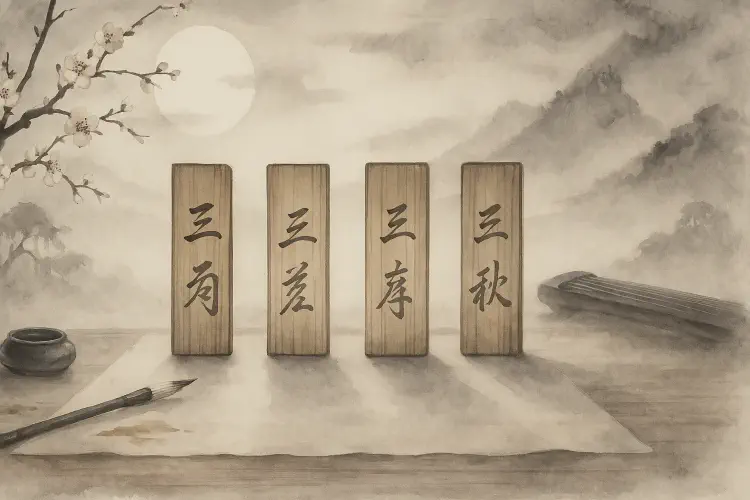

Role of classical texts in chengyu formation

Classical Chinese texts supplied the **stories, images, and aphorisms** that later crystallized into four-character **chengyu (成语)**. Understanding these sources clarifies meanings, registers, and proper usage.